What is an Autoclave and Why Do We Use It

It is always a danger to health working in a microbiology or pathology lab. In such laboratories where lots of work goes on with bacteria and virus, or possibly infected materials, the need for sterilization is paramount. The slightest chance of contamination from a ‘dirty’ apparatus can shut down a whole lab, and ‒ let’s hope not ‒ get someone deadly sick. This is where an autoclave comes in very handy.

Bacteria and viruses and living or semi-living things ‒ and as such, they can live within very specific boundaries only ‒ in specific environments. Unlike the glass beaker that held some bacteria culture, they won’t survive at high temperatures and pressure. And that is the environment you can create within an Autoclave ‒ very unfriendly to any kind of microorganism.

Autoclave Definition

According to Wikipedia, An autoclave is “a machine used to carry out industrial and scientific processes requiring elevated temperature and pressure in relation to ambient pressure and/or temperature.” So, what does that mean for a laboratory?

A laboratory that deals with microbes have a lot of glassware and apparatus that come in contact with dangerous bacteria and viruses on a regular basis. And cleaning them with just soap and water is not enough ‒ most microbes can persist well after even a good thorough cleaning. To really make sure all the contaminants are definitely killed, you have to subject them to heat ‒ and pressure.

An autoclave does just that. Think of it as a pressure cooker for lab apparatus. It basically ‘cooks’ various heat-resistant glassware and apparatus with extremely hot air or steam under high pressure for a good amount of time. The heat and pressure make sure all living or semi-living organisms (like viruses) die and disintegrate into harmless waste compounds.

Working Principle of an Autoclave

Also called a steam sterilizer, autoclaves are basically machines that create an artificial environment of high heat and pressure. Think of an autoclave like a high-tech pressure cooker ‒ inside which you cook your flasks, beakers, tongs, dissection tools, and such stuff ‒ that creates an extremely inhospitable environment for life. Kind of like on a very big planet very close to a star. An autoclave does this through the following structure.

Parts of an Autoclave

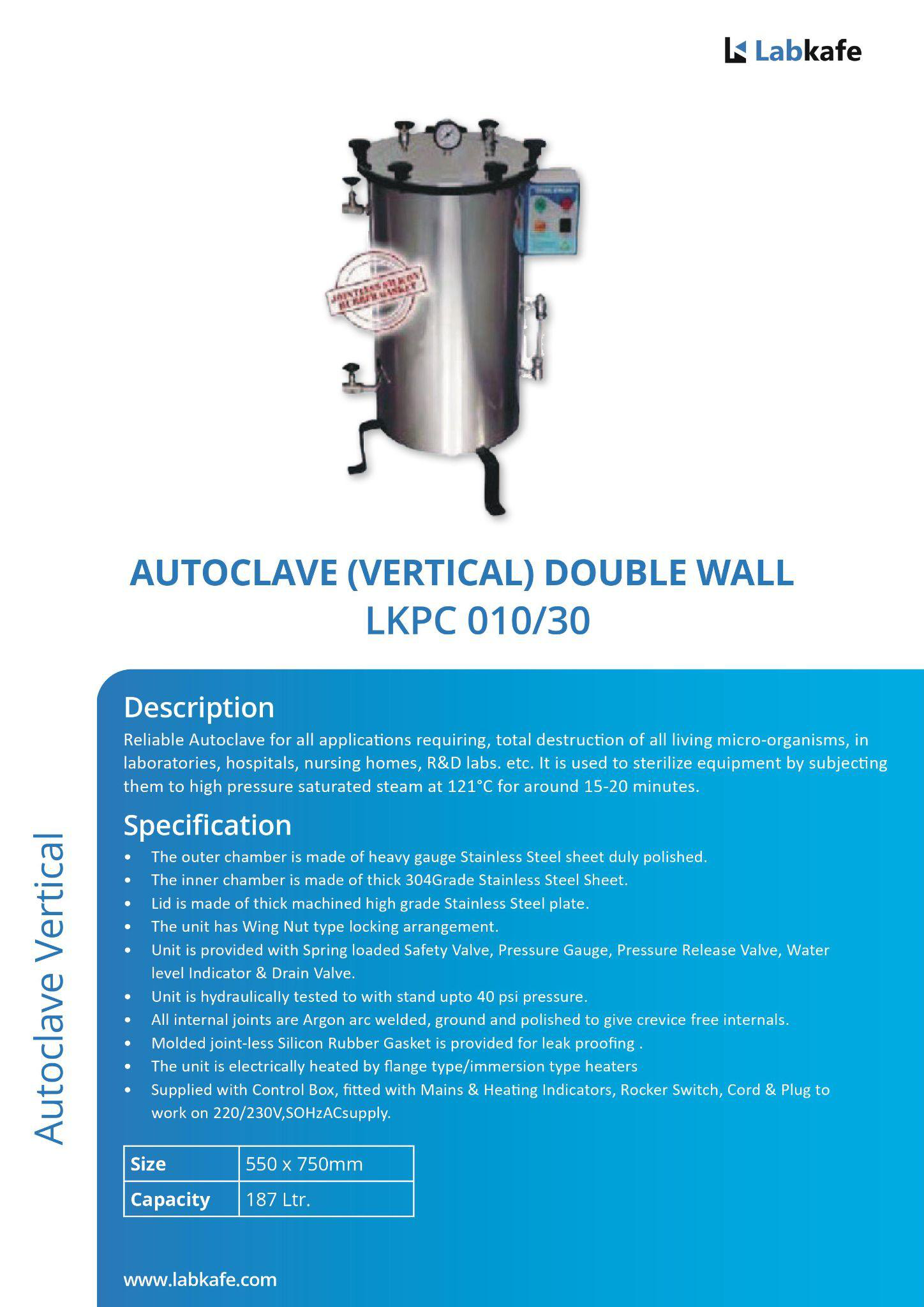

- Pressure Chamber: This is the main body of the autoclave. It has two parts ‒ an inner chamber, very hard and strong, and an outer jacket, also quite strong. Superheated steam flows through the space between the two walls of them. The inner chamber is often steel or gunmetal and the outer jacket is iron or steel. They can be as small as 10 liters or as big as 1000 liters.

- Lid or Door: As you can guess, the pressure chamber needs a lid or door to make it accessible for use. This can work on a hinge for bigger autoclaves, or can be completely removable for smaller ones (which are basically pressure cookers anyways). There would be screws or clamps to close the lid solidly, and an asbestos washer (large ring around the opening) to seal it airtight.

- Pressure Gauge: Working with high pressure is always dangerous and so you will need some way to monitor the pressure inside the chamber. The pressure gauge does this. It generally sits on the lid itself for smaller cases, or in the large floor-standing autoclaves it may be built-in. The meter can be analog for smaller ones, and digital for larger models.

- Release Valve: Obviously when you’re working with high pressure there would have to be an automatic pressure release system, ideally also warning you about the high pressure at once. The release valve handles this work, doubling as a whistle. Normally gravity-operated, this sits on the lid too.

- Safety Valve: Just like a good pressure cooker an extra safety valve is present on the lids of most autoclaves, just in case the normal release valve fails. It’s just a bit of hard rubber that bursts out instead of bursting the whole chamber.

- Steam Generator: All of the above would be pointless without the superheated steam itself, and a heater or steam generator takes care of that. You have to maintain a proper water level inside this, since too little water would burn the things and too much would fail the purpose.

- Wastewater Collector: You need someplace to let the excess steam and hot water go, and the wastewater collector is the place for that. Sometimes, it can cool off the water or condense the steam, before it hits the drain.

Video courtesy: Forsyth Tech CTL (Original video here)

How an Autoclave Works

The autoclave, funny enough, works with the same process as we use in our kitchens every day to cook hard meat. When proteins get heated above the boiling point of water, they coagulate into some biologically inert substance. But how do you subject something to high temperatures easily?

By boiling water under pressure. The relationship of boiling point with pressure is that the more pressure you apply on a liquid, the higher its boiling point spikes. Water is the most commonly accessible liquid on earth, and it boils at 100 degrees centigrade normally. But put more pressure on it and it gets hotter and hotter, but won’t boil. At 15 psi, you have to turn up the heat up to 125 degrees before you see the water boil. And this steam, of course, carries a lot more heat than water vapor at normal pressure.

When this superheated steam of 125-degree temperature hits any living organism ‒ i.e. a microbe clinging to the walls of a beaker, in present discussion ‒ it transfers all that heat to that microbe’s body. Now a curious thing happens. Much of any living organism is made of some kind of protein, and protein behaves badly in contact with heat. It loses its definitive structure that gives it the qualities of a protein, and gets condensed into some other shape. In effect, the “living” part of a living organism gets pounded out. And that’s how you kill germs, properly!

Though we should note here that some particularly determined and enduring forms of life, like endospores and archaebacteria, can still survive this level of torture. For them, a whole different kind of thing is needed ‒ we’ll talk about it later. Generally, you don’t have these issues with standard lab work at microbiology labs or medical labs.

Uses of an Autoclave

Autoclaves are a very common lab machine ‒ you can find one in almost any microbiology or medical laboratory. These labs use the machine for sterilizing their glassware and steel surgical apparatus. A tattoo or body piercing parlor won’t really be safe without an autoclave, either.

Other than sterilizing things, you can also process medical and biological waste in an autoclave before disposing of it to make sure the environment doesn’t get contaminated. A specific decontamination system exists that cures liquid waste of all contaminants.

Laboratories use smaller, vertical autoclaves; while hospitals and pathology labs may use bigger models that look more like a bank vault. Industrial usage of autoclaving sees even bigger chambers vulcanizing rubber and cooking composite materials. Some autoclaves get as big as holding whole airplane body parts inside ‒ making composite body parts.

You can grow some special crystals at high temperatures and high pressures only ‒ such as the artificial quartz they use in electronics. Parachutes and similar stuff are packed using the same technology as well, but I wonder if that machine can be called an autoclave or not.

How to Use an Autoclave

In general, most common autoclaves are run at 121 degrees centigrade for half an hour. The step-by-step instructions to run an autoclave are as follows.

- First, check for any stuff leftover from the previous cook. Also, as cleanliness is safety in any lab, make sure the autoclave is clean inside and out.

- Put a sufficient amount of water in the autoclave. How much water? That would directly depend upon the type of autoclave you’re using, its volume, and its structure. Do consult the supplied instruction manual.

- Put your glassware and apparatus to be cleaned in the pressure chamber of the autoclave. Don’t overload it!

- Close the lid or the door, and tighten the clamping mechanism (like the screws) to make sure the chamber is airtight and completely isolated from the outside environment.

- Adjust the pressure level valve screw on the lid for the intended pressure level. Make sure you don’t tighten it too much or the safety valve will blow.

- Turn on the heater and give it time to start boiling the water.

- Once the water starts to boil (you’ll see bubbles in the outlet), watch the discharge tube closely. As the inner air gets replaced with hot steam, the bubbling will gradually stop.

- As soon as that happens, it means the inside of the autoclave is full of only hot steam. Now close the drainage valve and wait for the pressure to rise.

- When the atmosphere inside the autoclave reaches the desired pressure level (controlled by the release valve screw), the release valve will blow its whistle and let the excess pressure out.

- The countdown of time begins now. When somebody says “run the autoclave at such-and-such pressure and temperature for 60 minutes”, they mean 60 minutes from the first whistle. Better start the kitchen timer now.

- When the time is over, simply turn off the heater first. Let it cool off to a decent enough temperature.

- Don’t open the lid yet! Instead, open up the discharge valve to let air in the pressure chamber. (Note: some smaller autoclaves don’t have drainage, in that case you can just open the pressure valve ‒ take care at this ‒ to let the steam out and let normal air in.)

- Now you can open the lid if it’s cool enough, and take out the things you’ve put in there.

Autoclave Types and Uses

As with most lab instruments, autoclaves come in many different shapes and sizes and structures. As mentioned above, they can be small pressure cookers to huge rooms holding whole vehicle bodies. Here are the most common types of autoclaves and their uses.

Benchtop Autoclaves

Also called pressure cooker autoclaves, these are the smallest ones out there, literally no bigger than a large pressure cooker. Some even come with an internal heater ‒ you have to mount them on some kind of hot plate or stove. As the name suggests, they are little more than just basic pressure cookers. It’s used in small labs for regular work, like in the pathology departments of small clinics.

Gravity Displacement Autoclave

The most common type, you can see this vertical autoclave in most microbiology and medical college labs. They have a steam generator separate from the pressure chamber. These are comparatively cheaper than most other types of autoclaves, being so common and easy to make.

B-type Autoclave (Positive Pressure Displacement)

A completely separate steam generator feeds the main body of the autoclave in this system, which is faster than most others since ready-made steam is available from before. This way, you can do multiple sterilization operations in quick succession.

S-type Autoclave (Negative Pressure Displacement)

This one has both a steam generator and a vacuum generator. The vacuum generator first sucks out the inner air before the steam starts rushing in. This is a great way to sterilize anything since there is no chance of outside air assisting life growth. So, if you need great accuracy of autoclave sterilization ‒ use an S-type one.

Other Types of Autoclaves

Generally all autoclaves you’ll see in use will work in one of the above ways, but they can differ a lot in shape and size. For example, the most common type of autoclaves are the vertical autoclaves but there are horizontal ones too. Some are compact and look as if a microwave oven and a cabinet-size vault fell in love and made a baby.

Some are large floor standing machines into which you can push in an entire trolly full of material to be cleaned. Some are lab workhorses suitable for frequent repetitive sterilization; some delicate ones again require a lot of maintenance or cleanup between usage. And all of them have some or other specific scenarios to cover. The laboratory equipment world is so awesome and complex, when you think of it!

External image courtesy: freepik

Leave a Reply